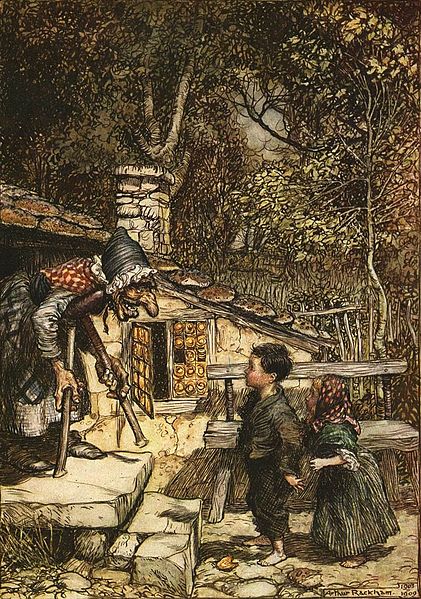

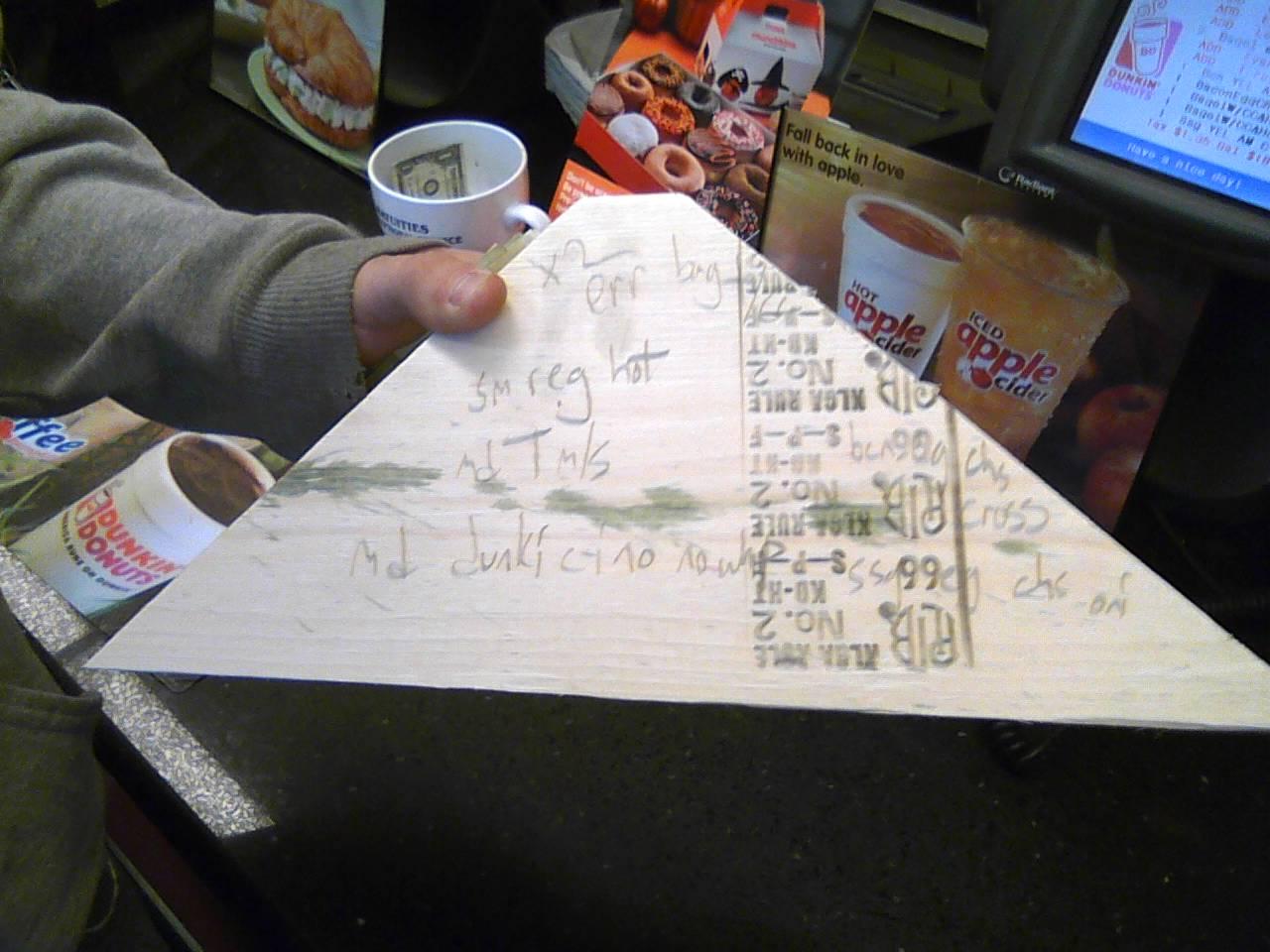

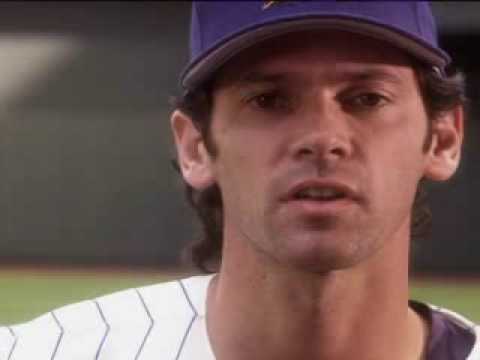

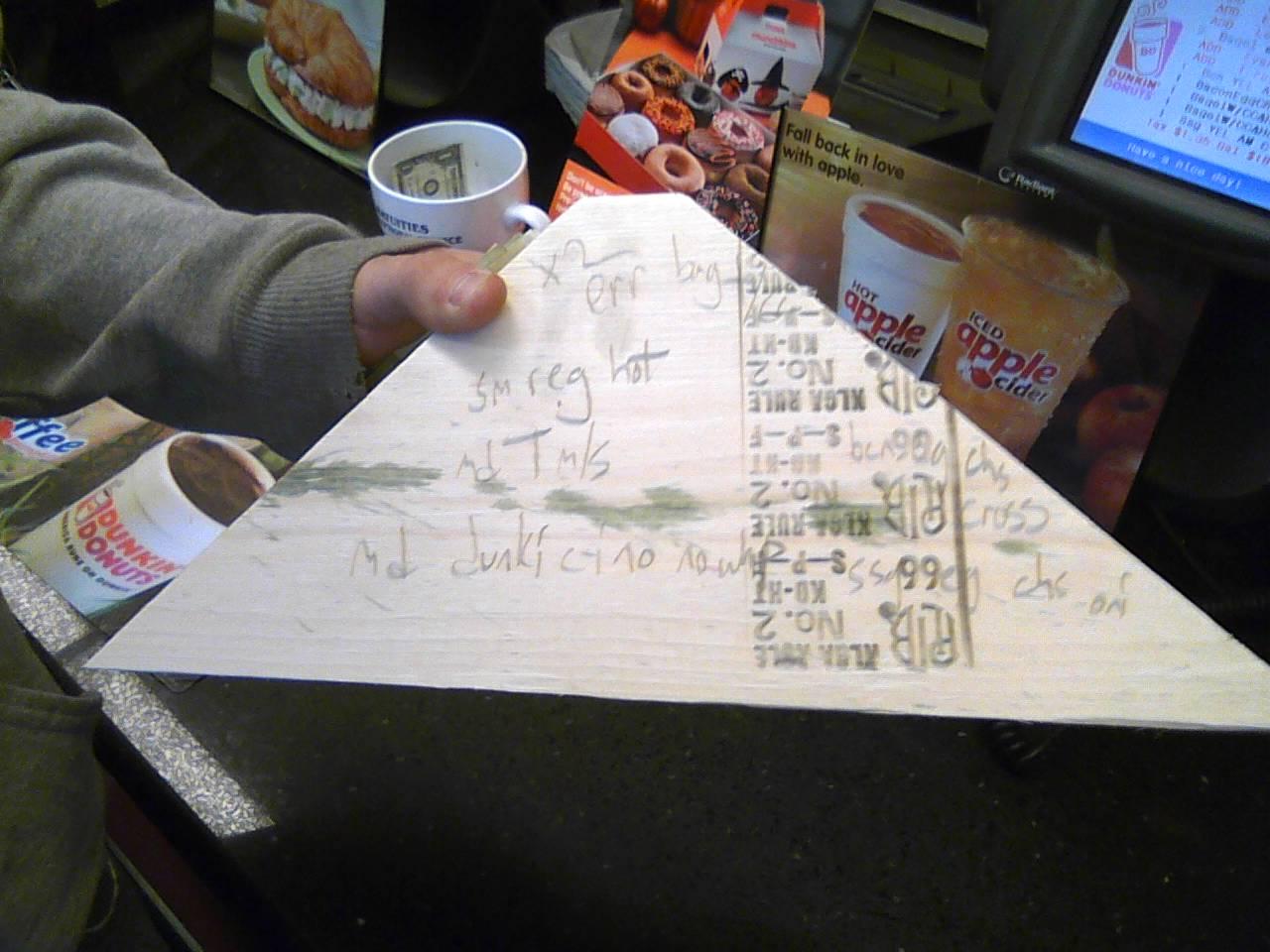

Earlier this winter, on a drive to Providence, I stopped at the Dunkin’ Donuts at the intersection of Routes 1 and 138, across from the site of the Hannah Robinson Rock and Tower, for an iced coffee and a chocolate-frosted doughnut. I got in line, ordered, and waited off to the side. The fellow behind me moved up to place his order, and presented the counter person with this:

"x2 err bag, sm reg hot, Md T m/s, Md dunki cy no," and so on.

“I can’t read that,” she said disappointedly.

“That’s okay, I wrote it. I’ll read it to you,” the fellow said.

He was wearing heavy-duty Carhartt bib overalls, Timberland boots, and a cotton hooded sweatshirt with frayed cuffs. He had just come from a work site, and he had written the coffee, tea, and doughnut order for the crew on a piece of scrap wood. The other counter help gathered round to admire his ingenuity, I took a photograph with my cellphone, and we all went our separate ways, smiling.

The odd, small beauty of this experience has lingered, and I think of it every time I approach that busy intersection. It’s almost as if an invisible strand of memory, like line unspooling from a reel, links me to that workman and that piece of wood, which is now, no doubt, long since burnt to ashes in a flaming pile of construction debris. And I thought of it again the other day when, having an appointment in North Providence, I saw this on a traffic sign:

The forward tilt of the head knocked me out more than the thought of an adolescent Andre the Giant in knickers.

I hadn’t seen one of these Andre the Giant stickers in a while, maybe because most of the thousands of them all over Rhode Island were slapped on more than twenty years ago and are weathering away. The brainchild of graphic designer Shepard Fairey, who created the image and the agitpop campaign to make it ubiquitous–as well as to promote himself and his brand–the Obey Giant phenomenon resides at the distinctly American intersection of conceptual art, anti-establishment cultural critique, and commerce. It’s a grand way to be subversive, be cool, and make money, all at the same time. What’s not to like?

Just a few days later, I read in the New York Times that Fairey pleaded guilty to criminal contempt for having concealed and destroyed documents as a means to cover his culpability in using, without permission, a 2006 photograph of Barack Obama by Associated Press photographer Mannie Garcia as the template for Fairey’s “HOPE” poster of the presidential candidate. Fairey had long claimed that he had not expropriated the AP image, so that he was not in violation of copyright laws. In January, 2011, Fairey acknowledged in a legal settlement with AP that “he had initially believed that The A.P. was wrong about which photo he had used, but later realized that the agency was right,” according to the New York Times. Now Fairey was admitting that he had tampered with documents to conceal his tracks and shore up his case against AP. He will be sentenced July 16 and could face up to six months in jail.

Whether the episode and possible jail time burnishes Fairey’s mystique and or takes him down a notch remains to be seen. It might accomplish both. Maybe he’ll have to drop the price of the Limited Edition Obey Pen and Card Case, a holiday gift idea on sale at his company’s website. “Your Mom or Dad will like the classic styling and never realize they’re a collaborator in the infiltration of the corporate world,” Fairey writes on the site, achieving a tone that somehow makes him both an instigator of mockery and an object worthy of it. Well, we’ll give him a break. He admitted his wrongdoing. He’s ready to take his medicine. And the Andre explosion, whose shock wave is still expanding after all these years, remains pretty cool at its heart–as Fairey has written, a nice introduction to Phenomenology, an attempt to “enable people to see clearly something that is right before their eyes but obscured; things that are so taken for granted that they are muted by abstract observation.”

With that in mind, get a load of this: an image that adheres to the surface of America’s Cup Avenue, in Newport, by the pedestrian crossing at West Pelham Street:

Alert Art Bell. Clearly, this is a sign from another dimension.

I saw this little guy, about six inches high, while crossing the street. It appears to be a vinyl cutout glued to the asphalt, but with the traffic and everything I didn’t get to touch it. This was the photographic remnant of a wonderful day of shopping and thirst-slaking in Newport shortly before Christmas with a group of friends who have known each other for more than forty years. We’ve been doing this annual jaunt since the mid 1980s, a grand tradition that never fails to yield up visual gems like this, another instance of the invaluability of the vernacular landscape.

Then, last week, one of the gang sends me this:

"A vinyl thingee pasted on the crosswalk at 44th St. and 6th Ave. in Manhattan," my friend Paul writes.

An online search quickly announced the creator of this image: Stikman, he calls himself. This little robot dude shows up all over the country and in a variety of forms, from pavement stickers to wood installations. Unlike the Andre image, which does not vary and whose potency, in part, derives from its graphic immutability, the variety of the robot’s posture and facial expression suggests not only a range of emotive qualities but the hand of different artists. When we slap on an Andre image, we’re participating in Shepard Fairey’s exercise in context busting. We become an extension of his physical silkscreen and of his metaphysical concept. But we can make our own robot dude, hence making the robot dude our own. It’s guerrilla graffiti of an entirely different, more accommodating sort.

The Brooklyn Street Art blog reproduces some nifty Stikman images, including this beautiful installation, Georges Braque by way of Louise Nevelson:

"...canyons of steel / They're making me feel I'm home." A Stikman figure in New York, in autumn (photo copyright Jaime Rojo)

More Stikman robots can be found here, there, and everywhere, the latter link posting some hauntingly beautiful wood installations in partial decay:

Photo copyright geko1973. Taken on March 5, 2012, in New York City.

By way of contrast, here’s an urban look at Obey Giant:

Photo copyright geko1973. Taken June 21, 2010.

In a most timely happenstance, Stikman is having an exhibition at Pandemic Gallery, in Brooklyn, New York, with an opening reception set for Friday, March 16. The show runs through April 6. Here’s the poster for the show:

"Celebrating 20 years of playing with sticks in the street." Note that Pabst Blue Ribbon is the corporate sponsor.

And here’s a portion of what the artist has to say about himself and his work, taken from the gallery’s website:

“My pieces start their lives as static objects, but they come to life when I place them in a public place where they are subject to the forces of time, interactions with humans and climate. I share this transient form of art to connect with a viewer whom I will never meet, in hopes that the joy of finding the unexpected has altered their consciousness. It finds an indigenous space in our surroundings like a flower escaping from the crack in a sidewalk. Continuously altered by time and circumstance.”

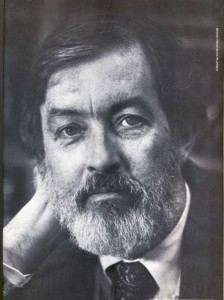

The joy of finding the unexpected. Perfect. And it brings us back to that piece of wood with which we started and on to the mind of a most extraordinary observer of American life, terrain, and culture, John Brinckerhoff Jackson, the author of Discovering the Vernacular Landscape (1984, Yale University Press) and many other revelatory books. I’ve not read a more incisive and provocative observer of the relationship between landscape and human activity. Though strictly speaking Jackson is a geographer, the breadth of his reading, the sensitivity of his eye, and his heart’s gracious acceptance of mutability make him more aptly a philosopher. After reading Jackson, the American landscape will never look the same–nor will little robot dudes.

Here is Jackson from the preface to Discovering the Vernacular Landscape: “I have wanted people to become familiar with the contemporary American landscape and recognize its extraordinary complexity and beauty. I have reminded them that their immediate surroundings, whether urban or rural, contain a wealth of structures and spaces and compositions no less impressive than those in other parts of the world and in many instances unique to America. Over and over again I have said that the commonplace aspects of the contemporary landscape, the streets and houses and fields and places of work, could teach us a great deal not only about American history and American society but about ourselves and how we relate to the world. It is a matter of learning how to see.”

To get an idea of the scope of Jackson’s influence, take a look at the books that have been honored with the John Brinckerhoff Jackson Prize, awarded annually by the Association of American Geographers, from Paul Groth’s Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in The United States to Arthur J. Krim’s Route 66: Iconography of an American Highway.

Jackson died in 1996 at the age of 86. According to his obituary in The New York Times, “After retiring from teaching and lecturing in 1985, he did laboring jobs at construction sites, gas stations and gardens.” Let us give him the last word on these matters:

“The older I grow and the longer I look at landscapes and seek to understand them, the more convinced I am that their beauty derives from the human presence. For far too long we have told ourselves that the beauty of a landscape was the expression of some transcendent law: the conformity to certain universal esthetic principles or the conformity to certain biological or ecological laws. But this is true only of formal or planned political landscapes. The beauty that we see in the vernacular landscape is the image of our common humanity: hard work, stubborn hope, and mutual forbearance striving to be love. I believe that a landscape which makes these qualities manifest is one that can be called beautiful.”