There’s a shopping plaza where it used to be. Driving south on Route 4, just as you cross over Route 102, you’ll notice an old silo tucked in on your left, barely visible by a stand of struggling trees, this small patch of green overwhelmed by the asphalt and cinder block that sprawls beyond it. A few steps southeast of the silo–that’s where the batting cages were. I kept extra tokens in the ashtray of my car so I could pull over and whack a few when the feeling struck. There’s a mile of difference between the way a baseball player swings a bat and the way the rest of us do. But that doesn’t diminish the pleasure of the occasional solid thwack and seeing the ball shoot over the torn netting and out toward the grassy field.

The peculiar joy of the batting cage–the creaking mechanical arm, the grunts and exclamations from adjacent batters, the expectation of each pitch, the final weariness and satisfaction–returned in a rush, along with many more of the unique charms of baseball, reading “The Way of Baseball: Finding Stillness at 95 mph,” by Shawn Green and Gordon McAlpine (Simon & Schuster, 2011).

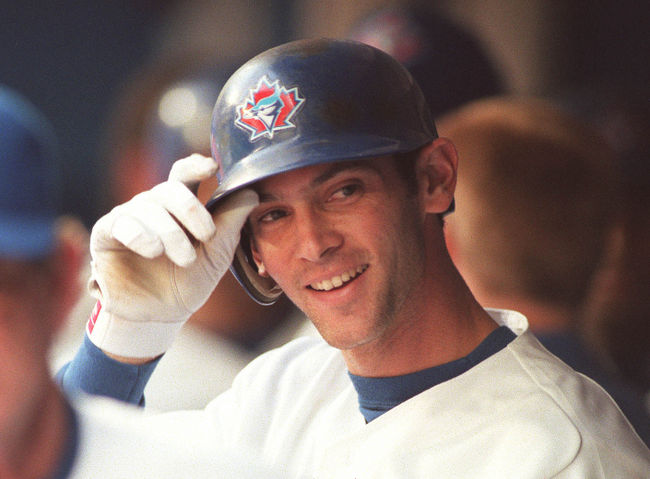

Shawn Green, who began his fifteen-year career with the Toronto Blue Jays, holds the major league record for total bases in a single game, nineteen, when he hit four home runs, a double, and a single against the Milwaukee Brewers on May 23, 2002. He's also the only major league player to hit seven home runs in a three-game span (May 23-25, 2002). He hit 42 homers that year, among the 192 homers he hit in a great five-year stretch from 1998-2002, when he was among the top hitters in the game. (google image)

“The Way of Baseball” describes the role of Zen meditation in Green’s journey to free himself from his ego, play baseball without the burden of goals, and learn to live in and savor the moment. It’s unusual and refreshing to hear a professional American athlete speak this way about himself, and it’s the first time I’ve finished a sports memoir reminded that the desire for perfection is an invitation to disappointment.

Green was in his third undistinguished season with the Blue Jays when manager Cito Gaston forbade him from using the batting cage unless it was in the presence of the team’s batting coach. They wanted Green, a left-handed hitter, to learn to pull the ball–that is, to make contact with the ball early and hit it to right field, increasing the chances of a home run. Green wouldn’t do it. He wanted to hit productively to all fields. In anger and frustration, Green started practicing on a batting tee, the only place he was allowed to take unsupervised swings.

"My breathing became rhythmic: inhaling as I put the ball on the tee, holding my breath as I got in my stance, and exhaling as I took my swing," Green writes. "What was happening here? My tee work had started out as form of punishment, yet suddenly it felt like something else, something more than just a hitting exercise. Was it becoming a meditation?" Green used a Tanner Tee, just like this one. (google image)

In time, Green found that his daily work with the tee was quieting the voice in his head and rewarding him with stillness. He learned, as one does in yoga, to focus on his breathing and not on the pose, to feel the swing without thinking about it. His practice gave him the confidence and the self-awareness to take apart his swing and burnish each of its components: his stance in the batter’s box, the length of his stride, the orientation of the head and eyes toward the pitcher, and the “loading” of the upper body–that is, the location and timed movement of the shoulders, arms, and wrists as the swing develops, among many other elements. Most important, Green came to see the pitcher not as an opponent but as a partner.

Green lingers in satisfying detail on how he rebuilt his swing over the next two years, deepening his meditation practice and stilling the natural tendency to be hard on himself. He is learning, as Buddha taught, that “You yourself, as much as anybody in the entire universe, deserve your love and affection.” Hardest of lessons, alas.

There are delightful observations on the era’s greatest pitchers along the way:

- “Pedro Martinez was untouchable in the late ’90s not because he threw harder than anyone else but because both his fastballs and off-speed pitches looked the same coming out of his hand. Such deception, along with great control and movement, makes it tough for a hitter to get the barrel of the bat on the ball.”

- “[Curt] Schilling’s glove started the same every time out of the windup, but when his glove went over his head, the fingers rounded on the forkball and remained flatter on the fastball. From the stretch, it was more difficult to catch, and I sometimes got crossed up because the differences were so subtle. Other times, I swung and missed even though I knew what was coming because Schilling had such good movement on his pitches.”

- “[Randy Johnson’s] tip was easy to discern because his glove flared before he began his windup…. In one game he grew so paranoid about us having his pitches that he altered his whole delivery by hiding his hand behind his back rather than keeping it in his glove as he normally did. I enjoyed seeing such an intimidating figure completely lost in his head.”

These tropes–of being lost in the head, over thinking, hearing the harping, critical voice of “the little man on my shoulder”–inform the book, becoming most dramatic after Green’s eventual success with the Blue Jays led to his signing a six-year contract with the Los Angeles Dodgers for $84 million. The pressure was on, and Green imploded.

“The pull of my ego proved too strong,” Green writes. “My awareness became lost in my new identity…. What I didn’t realize was that it was my ego that was pulling me out of the present moment at the plate. Instead of becoming the act of hitting, as I had in the past, I was working toward the purpose of fulfilling statistical goals. I calculated that I needed to hit about 7 homers and notch about 20 RBIs each month to stay on track with the player I was supposed to be: the star who’d hit 42 home runs and had 123 RBIs the season before.” Green finds a new understanding in a familiar Zen proverb: “Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.” Humbled by his disappointing performance in 2000, Green recommits himself to living in the present moment, rediscovers his swing, and lets go of ambition and goals. The process is nicely symbolized in a section on Green’s decision, on September 26, 2001, not to play on Yom Kippur, though not a fully observant Jew. The incident, of course, echoes Sandy Koufax’s famous decision to sit out a World Series game in 1965 because it fell on Yom Kippur. For Green, the decision allows him to display respect for his heritage and to sever a tie with his ego: missing the game ended a streak of 415 consecutive games and cost him a shot at hitting fifty home runs for the season. (He ended with 49 homers and 125 RBIs.)

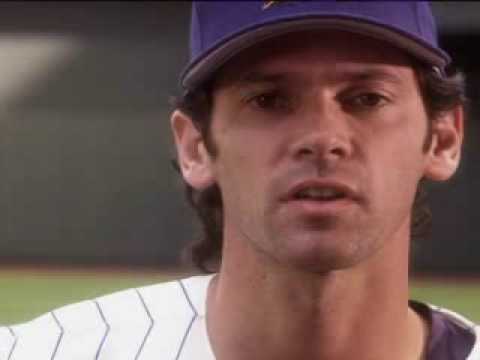

Here’s a look at Green’s swing, slowed down, as part of a television ad against the use of smokeless tobacco products. Green was with Arizona Diamondbacks at the time (2005-6). The swings starts about twenty seconds in. I’m struck not only by the relaxed grace of his swing but by the way he lowers his head at the moment of contact, as if bowing in gratitude.

Green’s account of his historic week in May 2002 is fascinating reading, all the more effective for his and co-writer McAlpine’s decision to chronicle each at bat with excerpts from Green’s journal entries, written after the games. What a stretch of hitting. Among the gems was a first-pitch home run against Schilling, with the defending world-champion Diamondbacks, marking Green’s seventh consecutive hit, five of which were home runs. In the next game, Green broke his bat on the last swing of his streak, hitting his seventh home run in three consecutive games, batting eleven for thirteen with fourteen RBIs. The cracked bat now rests in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, in Cooperstown, New York. And the satisfying memory of Green’s rewarding journey rests in me. Namaste, Shawn Green.