Unmet friends give us one last gift in their dying: the obituary. I am repeatedly reminded of this blessing in the fruitful pages of The New York Times, meeting artists whom I otherwise would never have discovered were it not for the curtain of death. So it was as I read the November 3, 2011, obituary of Mary Hunt Kahlenberg, an extraordinary woman, who died October 27, with her husband by her side, in their home in Santa Fe. Kahlenberg was an expert in the art of the Navajo blanket, the founder of what is now Tai Gallery/Textile Arts, in Santa Fe, and, during a long career as a museum curator and collector, a champion of textiles as art rather than craft. Her warm aesthetic heart, technical understanding of textile creation, historical acuity, and sharp eye for detail combine memorably in “Walk in Beauty: The Navajo and Their Blankets” (Gibbs Smith, 1991), which she wrote with Anthony Berlant. (The volume is available in Rhode Island libraries.)

Kahlenberg's study of Navajo blankets weaves the disheartening story of the tribe's forced relocation and incarceration with its indominable spirit, as reflected in the vivid patterns, colors, and emotive power of textile weaving.

The book is a wonderful portal to the artistic beauty of Navajo blankets, with key aesthetic points dramatically illustrated by full-page color photographs of the textiles. Kahlenberg’s observations are trenchant and confident.

“It is obvious that in the weaving of blankets, there is a tradition for complexity and control without equal in our culture,” she writes. “In their blankets, the Navajo had a visual language that enabled them to show each other who they were. The blankets were self-portraits in which the Navajo manifested their place among people, their integration with the landscape, and their oneness with the spiritual forces of life…. There was a dynamic connection between design and function–a Navajo blanket expressed the character of its wearer and give him a kind of permanent gesture….

“There are constants in the Navajo experience which underlie the tradition of these blankets. Foremost of these is a feeling of energy. It is as if each blanket were a diagram of the spiritual presence of an individual.”

Kahlenberg’s aesthetic is especially valuable as it bestows us with the new ability to engage with Navajo blankets as artworks rather than to simply see them as craft or utilitarian objects, to enter a created world as our perception and imagination dovetail with the tangible vision of the artist. Her careful explication of technique, cultural history, and evolving design features gives us the vocabulary–the tools–we need to apprehend and to feel in new ways. A great gift. She is also wonderful when explicating the role of abstraction in Navajo society–a trait deeply rooted in the tribe’s shared culture rather than the sole purview of “the artist,” as it is in our culture–as well as the creative freedom and independence of women, all of whom were weavers, in Navajo society.

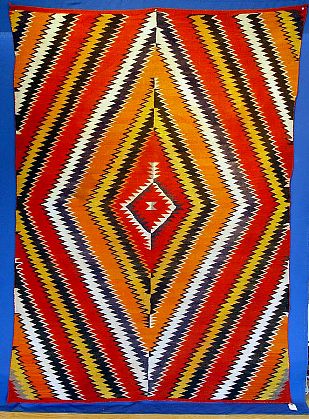

A splendid example of an Eye-Dazzler blanket, a style that emerged and flourished between 1875 and 1890. The name was given to these blankets by traders, in response to their explosive expressionistic urgency.

It must be fantastic to see these blankets up close. The blanket above, for example, is 80 inches by 57 inches. Astonishing. (It’s available here for $9,500.)

The Arizona State Museum organized an exhibition on Navajo weaving in 2004-5. The museum’s website offers a nice introductory history of the art, with slide shows and other helpful features. The exhibition also included the work of contemporary Navajo weavers.

One of the most fascinating features Kahlenberg discusses is the Navajo blanket’s lack of a border. On all four sides, the patterns move to the edge, go past the edge, and continue into infinity. It is as if the wearer becomes enclosed literally and figuratively in the unique vision of an infinite physical and metaphysical landscape. It was only later in the 1890s, when the commercial role and influence of traders grew stronger, that this never-ending quality gave way to the use of borders as a design element–indeed, a very emblem of the political enclosure of Native Americans. The traders were reacting to the wishes of the buyers of blankets who lived back East, who found the lack of borders upsetting, Kahlenberg notes.

So it is, thanks to the obituary, that we play a part in the continuation of a life well lived, leading it past an ending and toward a shared future.