“Well,” the driver said, “you invited him up here. Send him back.”

“He wouldn’t go,” Cogan said. “He’s hungry for the dough, said he really needs dough. Lost his job or something and everything. He wouldn’t go if I told him. I don’t think he’d do anything I told him, unless he was so drunk he couldn’t think of anything else to do. Which he probably is.”

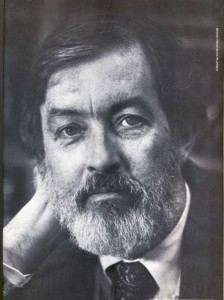

The first chapter of Cogan’s Trade, by George V. Higgins, is ten pages long, 310 lines of writing. Only twelve of them are descriptive, the rest dialogue among three characters. The rap on Higgins, who died at 59, in 1999, at his home in Milton, Massachusetts, was that he was great on dialogue–plot, not so much. This is bunk, and it irritated Higgins no end. Here he is in an interview with English writer John L. Williams, in 1989, from Williams’s Into the Badlands, a collections of his pieces on crime writers (the chapter on Higgins appears here):

“I have tried and tried and tried… I have had more success in your country than in my own. People want to be told stories and I have tried to explain, at what I’m sure is tedious length, that in my novels the characters are telling you the story. They do not understand. I am sick and tired of reviews that go ‘of course there’s no plot as usual but the dialogue is great.’ It’s as a friend of mine said when George Brett was still in his heyday with the Kansas City Chiefs, ‘Ah well, George Brett hit 350 again this year and George Higgins still writes good dialogue. You guys should start a club.’ I’m sick of it.”

Elsewhere Higgins noted, “Dialogue is character and character is plot.” So what is it about the dialogue? There is the slang of hoods, of course, but truth be told not much of it. There is the run-on sentence, too, with its paucity of commas and conjunctions, but that’s hardly a revealing technique. Profanity, contractions, hesitations, interruptions, digressions. All of these qualities add a patina, an kind of aural atmosphere, but they can’t carry the emotional weight or provide the forward motion of great writing. What can bear the burden and send the wind rushing past your ears as the story moves ahead is the way Higgins has his characters try and fail repeatedly to make sense of the randomness of their incomplete lives through storytelling. They are attempting to create an arc of meaning for what they do, for what they want and have wanted, dream and have dreamed of, as if the manipulation of words can impose order on reality–indeed, control reality. The extent to which Higgins’s characters are in self-delusion and the extent to which they remake their world is marked by their failure or success as storytellers. Each character drapes himself in imagery that springs from self-created stories about his past, imagery that accrues like the sweat and dust of a long day. Each character creates himself for others through stories, and the effect of those stories changes depending on who’s listening, who the character wants to complain to, impress, threaten, and control. Higgins’s characters, like Shakespeare’s, manipulate meaning by manipulating imagery.

Born in Brockton, Massachusetts, in 1939, Higgins earned a law degree from Boston College in 1967, after working for a time as a reporter for The Providence Journal and The Associated Press. He became a deputy assistant attorney general (1967-69) and assistant attorney general (1969-70) for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, assistant U.S. attorney for the District of Massachusetts (1970-73), and a special assistant U.S. attorney (1973-74), then turned to private practice as a criminal attorney. Of Higgins's first novel, "The Friends of Eddie Coyle" (1970), Norman Mailer said, "What I can’t get over is that so good a first novel was written by the fuzz."

And it doesn’t hurt that he’s so damn clever, as in this exchange between Cogan and a man we know only as “the driver,” toward the end of a brilliant fifteen-page conversation set in a silver Toronado that’s parked in an MBTA lot in Cambridge, from Cogan’s Trade (1974):

“Counselor,” Cogan said, “go talk to the man. Trattman’s gotta be hit, and you put it up to the man, he’ll agree with me right off. Give it a try. You don’t do it? Forget about the money. He made a mistake.”

“A long time ago,” the driver said. “He made a mistake a long time ago.”

“He made two mistakes,” Cogan said. “The second mistake was making the first mistake, like it always is. That’s all you get, two mistakes. Tell the man.”

Cogan is a hit man, called in to track down the three men behind the robbery of a mob-sanctioned, high-stakes poker game. Two of fiction’s most endearing, loud-mouthed blunderers are in the mix, Frankie and Russell, who, with Amato, nicknamed Squirrel, get the stories going at a fast clip in the novel’s tour de force first chapter. A film is in the works, written and directed by Andrew Dominik and set for a September release, with Brad Pitt as Cogan. The title has been changed to Killing Them Softly, not a promising sign. But the cast is to die for. Joining Pitt are Richard Jenkins, James Gandolfini, Ray Liotta, and Sam Shepard–enough testosterone to galvanize iron. The setting in the film has been moved from Boston to New Orleans. No doubt the city needs the help of an infusion of production money, but there is no scenic beauty in the novel, whose action is played out in a dreary succession of parking lots, apartment complexes, offices, and bars.

Coming off wonderful performances in "Moneyball" and "The Tree of Life," Pitt has been spared having to hone a Boston accent for the film version of "Cogan's Trade." They've moved the setting to New Orleans. Pass the Turbodog.

Films from two interesting novels for Richard Jenkins in 2012. Here, from "Cogan's Trade" and later in "One Shot," based on the 2005 novel by Lee Child, with Tom Cruise (as Jack Reacher), Robert Duval, and, gulp, Werner Herzog. I'm already in line for both.

Higgins describes Russell, on the book’s first page, as wearing “an army-green poncho, a gray sweatshirt and dirty white jeans. He had long black hair that reached his shoulders. He had the beginnings of a black beard.” So which generates more heat, those descriptive words or this dialogue:

“It’s stupid,” Frankie said. “It’s fuckin’ stupid. That’s a thousand dollars a year.”

“Look,” Russell said, “I don’t need nothing, make me dumb. You know that, you and Squirrel. Squirrel knows it, at least. Maybe you still think we were smart, doing that. You’re just as dumb as I am. You just come around and stroke me some, I’ll do any dumb fuckin’ thing you can think of. The thing is, though, you and me’re different. When this’s over, I’m through, doing dumb things for guys. I do dumb things for me, maybe, and then, I get grabbed, okay, at least I was doing them for me. Which means, I get to keep all the fuckin’ money. I don’t have to give Squirrel nothing for being smart enough to see I’m stupid any more.”

The defense rests.