That’s a word I hesitate to write this time of year, when summer is in full stride, the turf grass dormant, only the indomitable weeds plump and green, the compacted soil at the edge of the driveway as dense as granite, and the end-of-the-day sun at the beach so warm and comforting it deceives you into thinking that your skin will feel this way forever. Alas, it won’t. So it goes. Each passing day of August brings a postscript: one morning you will awaken, and you will know that summer’s over, the cool tingle of fall on your cheeks, a feeling so crisp and immediate that its sensation can never be undone no matter how hard you try to pretend it away.

I consider this after reading a passage from J. L. Carr’s extraordinary short novel, A Month in the Country, first published in 1980. I have a lovely, albeit paperback, edition published in 2000 by The New York Review of Books (courtesy of the Robert L. Caruthers Library at the University of Rhode Island), with a hilarious, touching, and indispensable introduction by Michael Holroyd, whose latest book, incidentally, is reviewed today on the cover of The New York Times Book Review. Here it is:

“Just before I bedded down I stood at the window. And he was right–the first breath of autumn was in the air, a prodigal feeling, a feeling of wanting, taking, and keeping before it is too late.”

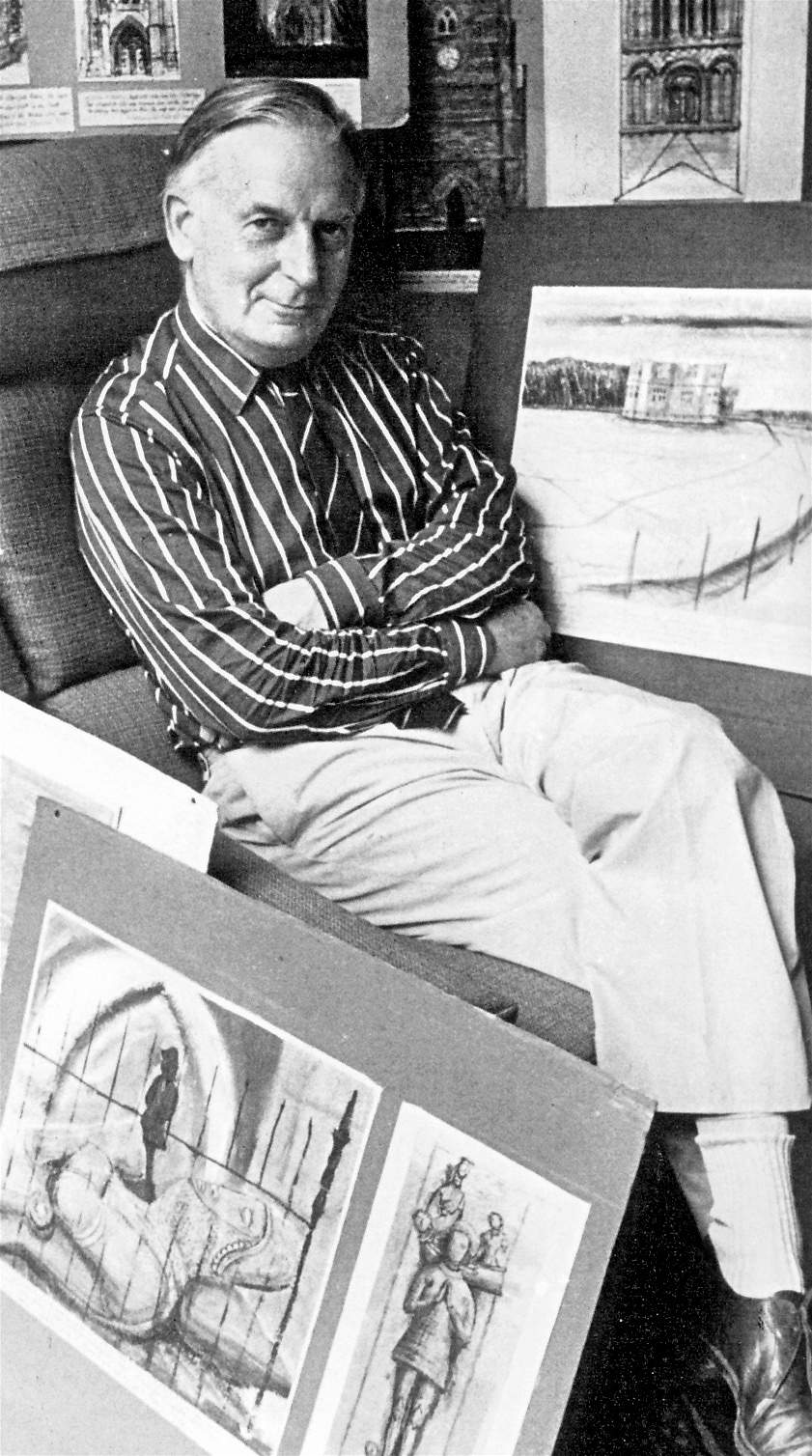

Born 1912, died 1994. When asked to define himself, he replied: "James Lloyd Carr, a back-bedroom publisher of large maps and small books who, in old age, unexpectedly wrote six novels which, although highly thought of by a small band of literary supporters and by himself, were properly disregarded by the Literary World." (google image)

The novel is infused from first to last with the warmth of rueful serenity. Written in the first person, it the story of a battle-weary World War I veteran, a talented young art historian and technician, who arrives in a small village in rural England where he has been hired to uncover and restore a Renaissance-era mural on the wall of a decrepit church. His time there spans a month, during which he makes friends, makes acquaintances, flows with the new rhythm of daily life, and, of course, falls in love. But falls in love in a way that is entirely his own, a love so heartbreakingly sweet and fragile, so poised at the edge of impossibility, that it fills your own heart with tangible joy and sadness. The narrative voice swells from the memory of the young man now old, looking back across the decades, wondering at what was, is, and might have been. As the image of the large, dramatic mural slowly comes into view from behind a centuries’ old wash of limestone, candle grease, and human exhalation, the narrator gradually finds himself identifying with the unknown artist, both his hand and his temperament, and this increasing artistic awareness dovetails wonderfully with the awareness of his new self, reborn after the horror of war through the balm of social intercourse and conversation, the renewing power of art and of a woman’s beauty.

Well. There it is. A book worth reading. Permit me to leap from macro to micro, and share a few of the words and phrases that compelled me to the dictionary while reading A Month in the Country. Like Shakespeare, Carr purposely peppers his story with words that are long gone from use, not only to tie it to an earlier time but also to deliberately separate it, almost physically, from the now time. It’s a way of saying, among other things, that all times are one time. Here we go:

the straw fish-bass

the narrow gate’s sneck

some Tactarian incumbent

seedcake

a largish oval escutcheon

sprinkle a little Keating’s once a week

kirtles and snoods

mullion

Bannister-Fletcher

I wouldn’t fancy being in the dock if he was the beak

rabbit pie

Despite the inclusion of the beloved leek in this recipe, there isn't enough money in the world.... (google image)

The Forgotten Garden

The Coral Island

Children of the New Forest

A platelayer crossed, pushing his bike along the path to the station

these fitments

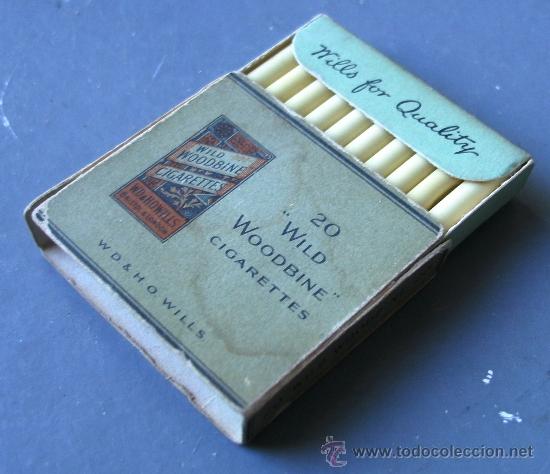

I lit a Woodbine

the Wesleyans

humping his estovers

hedges and spinnys

I will allow the so inclined to pursue these delectable phantoms on your own time. Me, I’m going to hump an estover by the spinny, after which I’ll light a Woodbine.